Like many people, I hate running. If I find myself in a position where I feel I need to move I’m much more likely to pick biking or hiking over it. Yes, I know it’s often more convenient to run, and yes, I know you can do it anywhere, but I just feel like it’s so much more exhausting than other forms of cardio. Despite my personal feelings on it, according to a CBS news article, “more than 60 million Americans own treadmills, and the number keeps growing each year.” However, its origins are far from a way to better yourself and release endorphins.

The early treadmill was called “the treadwheel” and was invented by William Cubitt, an engineer who was raised in a family of millwrights, in 1818. Two hundred years ago, England realized that treadmills were an easy way for inmates in prisons to get exercise while reflecting on their crimes (or at least, that’s what they said. In reality it was probably more about the labor and the fact that it kept them busy). Often, the treadmill would be hooked up to a grain supply, so corn would be milled via the work that they put in. Cubitt would go on to oversee the construction of the Crystal Palace in London in 1851, as well as become knighted by Queen Victoria for his work.

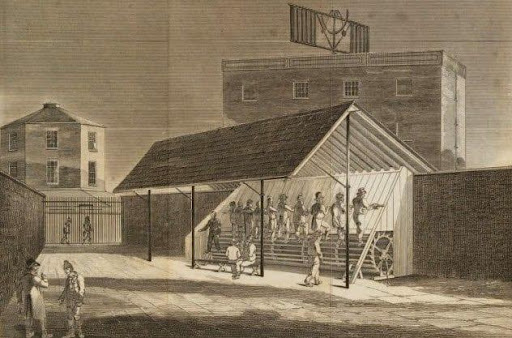

Like many inventions, the treadmill saw multiple forms, but the most popular was installed in Brixton Prison in London. There, prisoners would press their feet down on steps that were attached to a wheel, presenting them with another step, much like a Stairmaster you would see in a gym today. This treadmill-esque machine was also hooked up to a mill, much like earlier versions.

Just like that, the device took off across Britain prisons. More often than not, the machine could hold up to twenty-four prisoners, with partitions between them to cut down on socializing. In the summer, it’s been recorded that the machine would be running for ten hours a day, and in the winter it would be seven.

At the end of the eighteenth century, Britain began reforming its prison system. Initially, the prisoners had been provided with nothing, with loved ones having to visit in order to provide food and clothing. Not to mention that bribing guards was a very common way to ensure protection from other inmates. However, many wealthy people feared that the prisons would become “too cushy,” and resolved to offset this with pointless labor.

In order to keep morale down, treadmills were a part of this reform. They proved to be boring and exhausting, and while they started as a way to grind corn and pump water, they began to be used less as a working machine that served a purpose, and more as a torture device. By 1842, 109 of 200 jails in England, Wales, and Scotland were forcing inmates to walk on treadmills.

However, at the end of the nineteenth century, the focus among prisons shifted to mind over matter, and a series of prison reform acts began to restrict how long prisoners could be subjected to treadmills, with an act in 1898 calling for an end to them. By 1901, the astonishing 109 treadmills in prisons had dropped to just thirteen.

While the treadmill was being used in Europe, it also moved to the U.S. in 1822. Much like England, the U.S. faced similar problems with the treadmill, at first it was too harsh, and then it simply seemed pointless as the use for mills slowly declined. This being said, in the 1960s, the U.S. began to see an interesting take on the machine.

William Staub was an American mechanical engineer, who saw a market for the treadmill in those who ran for exercise but found it difficult to do so during the winter months. In the late 1960s, Staub created the “PaceMaster 600,” and he was hailed as “a pioneer in exercise, not for the athlete, but for the masses.” Staub began manufacturing treadmills, as we know them today, in New Jersey, and the phenomenon spread throughout the U.S.

I’m still deliberating over my opinion of the treadmill: Does its troubling historical background make it more interesting or more unappealing than simply running? To what lengths will I go to avoid treadmills, now that I know what they were invented for? (Did I just invent the world’s best P.E. excuse?) I think I’ll stick to hiking and biking, thanks.