In February, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York announced the return of a 2,700-year-old bronze griffin head to Greece. This artifact, dating back to the seventh century B.C.E., had been part of the museum’s collection for over seven decades, and the decision to repatriate the object followed an extensive investigation that uncovered its illicit origins.

The griffin head was originally looted from an archaeological site in Greece, before being sold to private collectors. In 1950, it entered the Met’s collection as a gift from a former trustee, a common practice among museums to acquire artifacts of shady origins through donations from wealthy patrons. This particular case of repatriation began when Greek authorities, working in collaboration with independent researchers, provided compelling evidence that the griffin head had been illegally excavated. The Met’s own internal investigation corroborated these findings, prompting the museum to take action. By voluntarily returning the artifact, the museum sought to demonstrate its commitment to ethical collecting practices and to maintaining positive relationships with countries seeking restitution of their cultural heritage.

The repatriation of the griffin head is not an isolated case, but part of a larger reckoning within the museum world. In recent years, The Met has faced increasing scrutiny over its collection practices. In 2022, New York law enforcement seized twenty-seven artifacts from the museum, citing their links to known antiquities traffickers. This incident, along with the ongoing global conversation about cultural heritage and historical accountability, has pressured institutions to take proactive steps in addressing the controversial provenance of their collections.

For Greece, the return of the griffin head is a victory in its long-standing effort to reclaim looted cultural artifacts. The country has been particularly vocal about the return of its antiquities, most famously in its demand for the Parthenon Marbles, currently housed in the British Museum. The griffin head, though a single artifact, represents a broader movement towards righting historical wrongs and restoring national heritage to its rightful place.

The Broader Context: Art and Colonial Legacy

The return of the griffin head must be understood within the larger context of cultural artifacts that have been removed from their places of origin, often under questionable circumstances. During the colonial era, many objects were taken from occupied lands and brought to institutions in Europe and North America. Some of the world’s most prestigious museums—primarily the British Museum, but also the Louvre, The Met, and many other institutions—house vast collections of foreign objects acquired during periods of imperial expansion.

Similarly to the Parthenon Marbles, another important example are the Benin Bronzes, a collection of intricately cast plaques and sculptures that were looted by British forces in 1897 from the Kingdom of Benin in present-day Nigeria. These artifacts are now scattered across museums and private collections around the world, with the British Museum holding the largest share. In recent years, several institutions have pledged to return some of these pieces, with Germany handing over two Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2022 and the Netherlands planning to return looted artifacts to Africa.

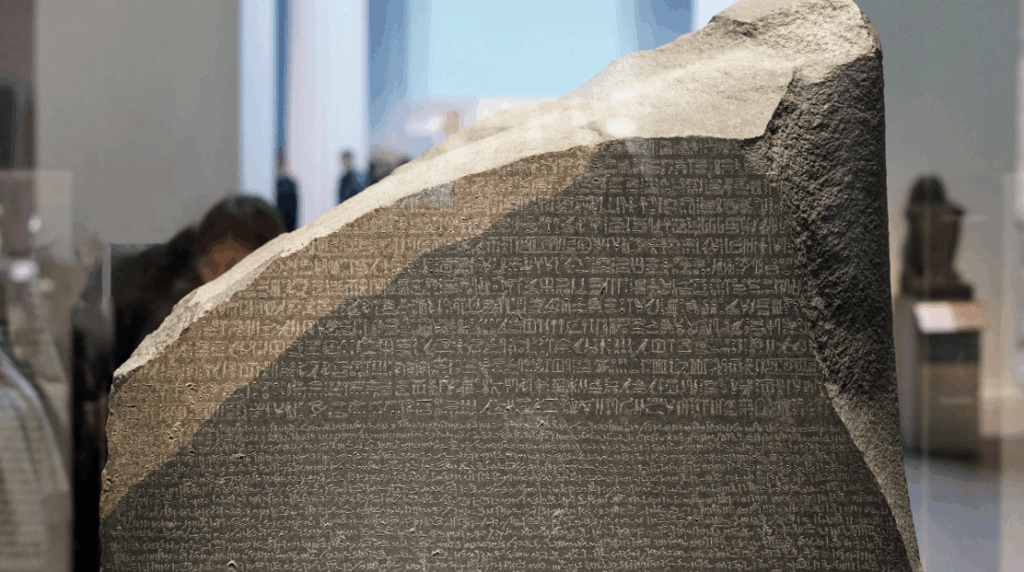

Similarly, Egypt has long called for the return of the Rosetta Stone, currently in the British Museum (spotting a pattern?), while Ethiopia has requested the return of treasures looted by British forces in the nineteenth century. The global push for repatriation has gained momentum, with activists, scholars, and even governments demanding that museums reassess their collections and return any objects that were taken unjustly.

The Debate Over Repatriation

The debate over whether museums should return artifacts to their countries of origin is complex and multifaceted. On one side, proponents of repatriation argue that cultural objects belong to the communities that created them. These artifacts hold deep historical, spiritual, and national significance, and their removal often represents a legacy of exploitation, cultural erasure, and disrespect. Restitution, they argue, is not just about returning physical objects but about acknowledging historical injustices and restoring cultural identity.

In the case of the griffin head, returning the artifact to Greece allows the country to reclaim a piece of its ancient history. For Greek archaeologists and historians, the object’s rightful place is in a museum or site within Greece, where it can be studied in its proper historical and cultural context. This argument extends to many other cases, such as the Parthenon Marbles, which Greece has long contended should be reunited with the rest of the Acropolis sculptures in Athens.

On the other side of the debate, some argue that major museums serve a universal purpose, preserving and displaying artifacts for the benefit of all humanity. Proponents of cultural internationalism contend that objects in major institutions like the Met or the British Museum are well-preserved, widely accessible, and serve as educational tools for a global audience. They also argue that returning artifacts could set a precedent that would empty major museums of some of their most significant collections.

However, this argument is increasingly being challenged, especially in cases where artifacts were acquired through looting or illicit trade. The griffin head, for example, was not obtained through a legal or ethical process, and its return signals a growing recognition that museums must take responsibility for the provenance of their collections.

Moving Forward

The return of the griffin head to Greece represents a shift in how museums approach cultural heritage. Institutions are increasingly starting to work with source countries to identify and return looted or illegally acquired artifacts. This trend suggests a move toward a more ethical approach to museum collecting, where provenance research plays a critical role in acquisitions and existing collections are reassessed with greater scrutiny.

The repatriation of the griffin head by the Met is a significant moment in the ongoing conversation about cultural restitution. While a single artifact, its return reflects a broader shift in the museum world as institutions confront their histories and respond to growing demands for accountability.

The question of where artifacts belong is not easily answered, but the griffin head’s journey back to Greece is a testament to the evolving understanding of cultural heritage. As museums reassess their collections and work towards ethical solutions, the future of global cultural exchange may become one that respects both the preservation of history and the rights of the cultures from which these artifacts originated.

Be First to Comment