Thousands of Chinese children, especially young girls, have felt a sense of awe and empowerment upon seeing an Asian face after the Disney logo of Mulan (1998). It is, of course, a watered-down version of the original ballad, but then most adaptations are. Nevermind the fact that the timeline was off, the clothing inaccurate, and the depictions of both the Chinese and the Huns based blatantly on stereotypes, there was finally someone that looked like them on the screen!

This tale has been told for nearly two millennia as the Ballad of Mulan, which tells of a woman named Mulan who took her aged father’s place in the military draft by disguising herself as a man. She fights in many battles and builds a distinguished reputation in the army. After her time in the militia, the emperor offers her a position of high prestige working alongside him. Mulan declines this proposition and decides to return to her hometown. She eventually reveals her true identity, causing astonishment in many of her peers.

Disney’s 1998 Mulan translated the tale beautifully, if not accurately in a historic sense. In no way did the animated version place her above or below men; she started out as a terrible soldier, like every other new recruit. They improved together in a training montage to “I’ll Make a Man Out of You,” and the film makes a point to direct our attention to the way she progresses from only appearing as a bride-to-be into a person in her own right.

In the opening scenes, Mulan displays numerous instances of ingenuity. Although many are played for laughs, like her cheat-sheet tattoo and feeding the chickens by having her dog drag around a bag of grain with holes poked into it, she also finishes a strategy game being played on the side of the street, figures out how to climb a training pole using weights to help rather than hinder, and uses artillery to wipe the Hun army out in an avalanche rather than simply opening fire. Her final fight with the leader of the Huns sees the use of a folding fan to disarm the latter. The movie emphasizes that, while she has learned the same abilities as every soldier, Mulan assesses whether strength or strategy would best suit each situation and acts accordingly.

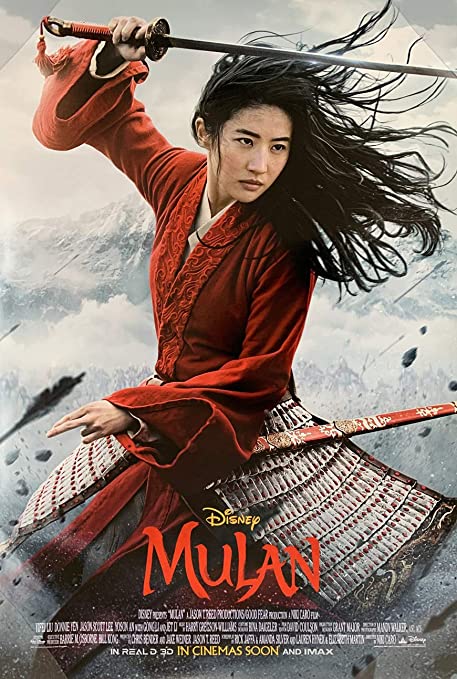

What the live-action Mulan (2020) made of that is, from a writer’s standpoint, a mess. The audience is introduced to a girl of elementary age that wields her limbs like weapons, and her weapons with prodigious ability. This sends a completely different message from the prior adaptation: only some females are worthy of being considered equal, and others like Mulan’s one-dimensional sister are not. It also undermines equality from the opposite angle, by having her constantly best men when it comes to training. Similarly, instead of the training pole, the recruits are instructed to climb stairs up a hill with two buckets of water hanging off their shoulders. There are no displays of working smarter rather than harder when it would benefit her to do so- instead, Mulan simply climbs the whole thing and “out-manly”s the men. Rather than feeling empowered, the audience subconsciously registers the unrealistic feats and fails to further connect or relate with the main character.

This story was traditionally about honor; serving one’s homeland by being willing to sacrifice oneself. The story was blatantly patriarchal, serving the older Chinese cultural tradition of preferring to conceive men rather than women, and unfortunately resonating with modern Chinese man-woman population ratio gaps and gender politics. Thus, the undercurrent of the story changes as well. The concept of filial piety is an old one in Chinese culture, one still practiced in modern times, if to a different extent. The social pressure shown in the song “Honor to Us All” shows one side of this, and the gifts that Mulan presents to her father is an attempt to bring honor to their family in her own way. However, the animated version also subtly addressed a concept even older and practiced in a range far wider than filial piety: the patriarchy itself. The Ballad of Mulan as it is taught in Chinese schools today incorporates a certain amount of propaganda, as do many old tales from other countries. Disney initially worked around it beautifully by having Mulan save the emperor not because he was her leader, or because it was her duty to her country, but because he was a fellow human in need of help. The only patriarch she would submit to freely was her father, and Mulan kneels before him at the end of the movie in respect for the one who provided for and raised her.

An American live-action remake with a focus on Chinese culture was inevitably going to face heavy criticism, but Disney took it one step further. Not only were the four listed writers all white (IMDb), but so were most of the crew. Critical roles to a cultural piece like this include the costume designer, set decorator, and the art department, but the names listed in the credits are overwhelmingly non-Asian. The result is what netizens consider a disrespectful imitation of Chinese culture. For example, the original tale tells of a girl in the 5th century CE born in northern China, yet the film shows Mulan’s home as a tulou house from the southern Fujian province nearly a thousand years later in the Ming Dynasty. The scenes of her hometown were, in fact, filmed in Fujian, to the confusion and outrage of anyone with a bit of knowledge in geographic history. The main antagonists of the movie are the Huns, and the plot involves Mulan defending the northern border from them. One post on Weibo—“China’s Twitter”—wryly jokes, “I guess Mulan has to take the subway out to join the army?” (variety.com).

Another complaint is that filming took place in the Xinjiang region. As a foreign company, Disney would have needed to ask for permission to film there, and the credits thank the Chinese Communist Party of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Committee at the end. However, it is known worldwide that Xinjiang holds about a million Muslims in concentration camps, and filming there only added fuel to the fire.

On top of that, the main actress Liu Yifei has expressed controversial views on the protests in Hong Kong. Various news outlets and civil rights activists worldwide have condemned the excessive force used by Hong Kong police on protestors, yet Liu wrote on Weibo in August 2019: “I support the Hong Kong police. You can all attack me now. What a shame for Hong Kong.”

With mindless critics calling it “the best Disney live-action adaptation so far” before release (insider.com), it puts into question the validity of Disney as a modern arts/entertainment company in the present landscape of cinema. With the new Lady and the Tramp, Dumbo, The Lion King, and now Mulan (all 2019/2020 films), Disney seems to be lazily recycling stories even more than usual in recent months. Ever since the death of Walt Disney, the company underwent severe changes with intention and purpose as an entertainment company.

With a history of creating immersive universes starting with shorts of Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie (1928) to Donald Duck in The Wise Little Hen (1934), Walt Disney’s early success in directing and producing features during his career built his and his brother’s production company into an industry powerhouse. This enabled countless dreams to be realized and seen by curious audiences everywhere. The Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio soon became Walt Disney Productions and money started to swarm in. After years of repeated success of moving audiences worldwide, Walt Disney eventually passed away.

Following his death, the company lost Walt’s vision and struggled to find its voice. The board eventually decided to let the company just rest on its new theme parks and its first wave of money-grab films that are critically scrutinized today. With this, Walt Disney Productions became the Walt Disney Company. With this era the animation division began to fade away. The animators grasped for life by having another renaissance with several films including Robin Hood and The Aristocats. This last-ditch effort to save themselves wasn’t granted by the higher-ups as they deemed the features weren’t financially successful enough. The company’s decline was interrupted by a brief period of success with new CEO Michael Eisner revitalizing the product. But with Chief Operating Officer Frank Wells’s death in 1994, the loss of his perspective caused some questionable decisions to be made—creating tons of new sequels to classic Disney films, such as Bambi II, Leroy and Stitch, and The Lion King 1½. With several more failures reminiscent of the Pre-Eisner era, money once again began to dictate creativity rather than the other way around. With this, Robert Iger stepped into his current role as CEO. Iger’s direction of the company mainly revolved around dominating the market by absorbing other entertainment companies and working towards a monopoly.

As a result of these efforts, Disney now controls over 40 percent of the film industry (CNBC) having a hand or ownership in many companies including the news networks ABC and ESPN, motion picture companies Marvel and Lucasfilm, and record label Hollywood Records (titlemax.com). This effectively classifies them as having an industry monopoly, being able to produce high quantities of content at lower costs due to their resources without fear of competition. Because of this, Disney doesn’t have to produce high quality films. With this, they only are willing to create what seemingly generates money, meaning they don’t passionately help create pictures that could touch the hearts of folks around the world if they don’t have to. While this creative issue can be traced even back to Disney’s golden era, more recently their films have become more pandering rather than substantial (evident with Mulan), using artifacts of nostalgia or using marketing to create a superficiality that would drive home financial success. The few acceptable products that come out from under Disney are only due to their constituent studios having creative control over their own media due to them having a found proper audiences and thus financial security. This stability allows and sometimes motivates Disney to exploit audiences by creating pandering content rather than fostering new and more original creative work. With this business model, the CCP’s influence on the new Mulan could apparently be accepted by the current Disney Company, if they found the film wouldn’t damage their superficial reputation and how much Mulan (2020) would accrue in the box office around the world.

With its desperate attempt to make up for the lack of a theater release, it overcharged curious viewers $30 for just a short period of time to be able to see the film. With the streaming takeover and the effects of the pandemic on how films are traditionally seen, Mulan (2020) managed to profit despite its negative audience reception and reception. Disney’s economic decline is still evident with Bob Iger’s motive to “save the company.”

Mulan’s failure to uphold the original Disney film’s legacy sparked massive backlash from Western viewers, and its typical Western orientalism led it to offend Chinese audiences as well. With its pitiful performance at the box office so far and now unlikely future theatrical release, modern Disney’s faults are revealed to outweigh Walt’s legacy. The future of Disney and film is at stake, and if a monopoly with such vast wealth in resources isn’t able to bring out new talents in the industry, this newfound cultural failure will either eventually force Disney to change or surrender due to their profit-hungry methods backfiring in the end. Searching for the cause of Mulan (2020)’s creative failure leads back to Disney’s history. With Disney becoming more and more of a corporate conglomerate with Disney+, its efforts to expand aren’t driven by Walt’s creative morals, but what gets seen and purchased in the modern era.

With this contrast between two films of two eras, and in the midst of the 93 percent decline in profit (barrons.com) the company faces, this failure reveals the dark and depressing truth about the production of arts and entertainment in the age of couchside consumption.