The election of 2016 left many of us wondering why the candidate who was ahead by nearly three million votes still lost. How does it make sense that, in one of the world’s leading “democracies,” someone can become president without popular support? The aftermath of that election was dominated by feelings of despair for the majority who felt their votes made no difference.

A stressful four years later, many Americans spent the 2020 election season biting our nails as we constantly refreshed our browsers, desperately hoping to win those crucial “swing states.” For me, it was a time of profound reflection on our supposedly democratic elections. Clearly, we choose our leaders through convoluted processes, and I wondered who those systems serve. Once I looked into it, I was shocked that such antiquated institutions still exist.

The system that facilitated the nonsensical 2016 outcome is known as the Electoral College. The Electoral College is a convention of 538 people who meet once every four-year election cycle to cast their state’s ballots for the next president. A state’s representation in the Electoral College directly corresponds to the number of Congresspeople (Members of House and Senate) from that state. This policy of representation is problematic. While one of the two branches of the U.S. Legislature, the House of Representatives, has representation for each state proportional to its population, each state gets two Senators regardless of population size. This results in a person from Wyoming having approximately 70 times the influence in the Senate as a Californian. If that sounds unfair to you, it’s because it is. In present-day America, every vote counts, but some count considerably more than others.

Was this inherent inequality part of the Founding Fathers’ vision? Well, actually, yes. The Electoral College is a rusted relic conceived early in the development of a young and tortured America. At the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the Connecticut Compromise gave rise to the bicameral or two-branched legislature that we have today, as well as the proportional representation in one house and not the other. States with larger populations evidently benefited from proportional representation, but states with smaller electorates demanded equal representation regardless. That same year, the Three-Fifths Compromise was passed, stipulating that enslaved people would be counted as three-fifths of a person for both representational and fiscal purposes. Consequently, the votes of people in states with larger enslaved (and therefore disenfranchised) populations carried extra weight, as those states had oversized numbers of representatives for their actual electorate. This is strikingly similar to the modern phenomenon of prison gerrymandering, in which incarcerated (and therefore disenfranchised) people are counted as residents of the areas in which they are imprisoned, inflating the voting power of the few residents of those areas who can actually vote.

We’ve since repealed the Three-Fifths Compromise, for obvious reasons. But for some reason, the inequality created by the Connecticut Compromise persists. States with small populations are still overrepresented in government and voters from smaller states have more power. If we were to take steps toward true democracy, disproportionate representation would be entirely eliminated. A decisive step toward this vision of true democracy would be to abolish the Electoral College.

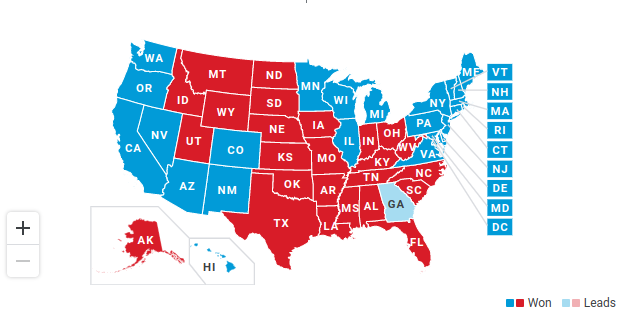

One of the reasons a candidate can become president without popular support is the winner-take-all nature of the electoral system. All electoral votes from a state are promised to whichever candidate obtains a majority of votes in that state. This means that even an incredibly narrow state victory can result in a major shift in electoral totals. If a candidate were to win in California by a mere 1 percent margin, they would already have 55 electoral votes towards a decisive majority of 270. Two states split electoral votes, but even that isn’t a comprehensive solution, but even with this policy, the issue of proportional representation still exists. If electoral votes were split according to the percentages of the vote each candidate received (as they would be if electoral votes were split in states), there would still be a discrepancy between a state’s population and its number of representatives, and voters in thinly populated states would still hold disproportionate power.

The winner-take-all system is part of why “swing states” are so crucial to electoral outcomes and why candidates routinely ignore states who usually vote strongly one way or another while on the campaign trail. If a candidate wins in any state that doesn’t split electoral votes, any percentage of the vote the losing candidate received will be effectively wasted. Therefore, most candidates decide that it isn’t worth the effort to campaign in a state where their opponent is strongly favored. However, even a slight victory in a swing state can warrant a major advance, and as such, candidates heavily campaign in swing states. However, if we were to abolish the Electoral College, candidates would be forced to win over voters all across the country, not just in six or seven “swing states”.

Another risk of the Electoral College is the possibility of electors voting for a candidate who did not win a majority in their state. Throughout history, there have been 157 of these “faithless electors,” and there’s little to no penalty for them voting as they wish and defying the will of the people of their state. This brings up a broader issue with the Electoral College. It concentrates too much power in the hands of a tiny group of people—people who have their own identities, biases, and political ideologies.

The elections of 2016, 2000, and others exemplify that the current system does not always result in a president chosen by the people. This in itself is an insult to democracy. Some may say that the current system doesn’t result in mismatches too much of the time, but even one four-year presidential term can wreak absolute havoc on a nation’s infrastructure. A president can cause damage that outlives them. In addition, the idea of switching from the Electoral College to a popular vote has popular support—61 percent (or about three-fifths, coincidentally) of Americans are in favor, according to a 2020 Gallup poll.

Implementation of a nationwide popular vote has never been easier to achieve. The best known legislation for accomplishing this is the National Popular Vote Compact, which 15 states, including New York and the District of Columbia, have already signed on to. These states have 196 electoral votes, 73 percent of the way to the electoral majority they need. If just a few more states enact this legislation, it will have real political weight and the remainder of the nation will be forced to reckon with the legitimacy and relevance of the current electoral system. All throughout history, the Electoral College has ostensibly served little purpose except to disenfranchise certain populations and elevate others, tweaking the political balance to favor elites who lost popular support ages ago. The Electoral College is a vestige of an America we’re still struggling to leave behind, and must be dispensed with if we are to make strides toward true democracy.