In our increasingly mechanized world, sustainable, equitable, and humane agriculture is a growing issue. I was born and raised on a small family farm in Caroline and live in a first generation farm family, meaning that we were beginning farmers not too long ago. We are still novices when it comes to some aspects of farming, but I learn a new thing every day, whether that’s how to effectively treat deer worms in goats or properly harvest basil leaves. But most importantly, I can speak to the difficulty of starting a farm from scratch. The toughest times are during the establishment of a farm rather than the maintenance. It takes incredible effort to secure the infrastructure one might need to house animals or grow crops. Unfortunately, the sad truth is it is even harder for farmers of color trying to stake ground in the small-scale farming community.

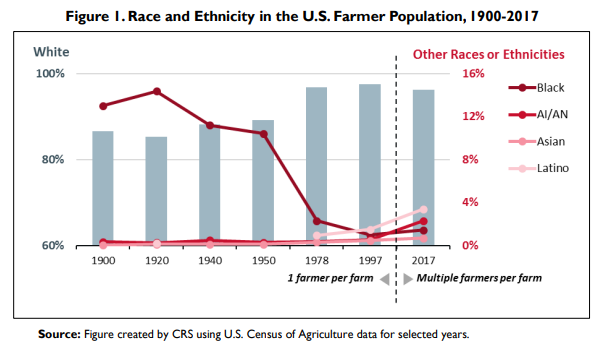

The total number of farmers in the US decreased by around sixty-seven percent between 1900 and 1997, which can most likely be attributed to the revolution of farming mechanization that promoted industry farming, not small-scale farms. In this same time period, the number of Black farmers decreased by ninety-eight percent. Although there has been a slight increase in these numbers between 1997 and 2017, there is still much to do to address the staggering dominance white farmers have in the agriculture industry.

Juliana Quaresma is the executive director of Groundswell, an Ithaca-based nonprofit organization that works to improve agricultural education, availability of local foods, and food justice in our area. She offered a lot of insight into societal barriers that people of color have historically faced when trying to farm. She explained that “historically, a lot of people of color have had their farmlands taken from them and have been deprived of access and opportunities to accumulate wealth.” Farming, being one of the least accessible ways to gain wealth, became one of the hardest avenues for success for people of color.

Land access and land theft continue to be major barriers to accessible farming for people of color. Currently, ninety-eight percent of private agricultural land in the US is owned by white farmers. Over the past century, Black farmers have lost over ninety percent of their land because of systemic discrimination and cycles of debt, according to Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) Mornings. These statistics reveal that farmland ownership has been dominated by white farmers. “Farmland ownership is a major component of farm wealth,” stated the Congressional Research Service on Racial Equity in US Farming. Owning farmland provides financial stability to a farmer by allowing farmers to accumulate wealth as the value and price of the land increases and use land as collateral when the farmer may need credit. Although grants and loans exist that can assist in securing farmland, they are hard to access and are extremely competitive, little support is in place to aid the financial process, and farmers of color face rampant discrimination. The Congressional Research Service claimed that there were instances in which farmers of color were “denied loans and subject to more stringent loan and land sale terms than white farmers, as well as landowners refusing to sell land to creditworthy farmers of color.” Lack of assistance from the Farm Service Agency, long loan processing, and misplacement or delay of applications all contribute to discrimination facing small farmers.

With recent revolutions in mechanization, it has become nearly impossible to run a functioning farm and not interact with expensive equipment such as tractors, bailers, trucks, and irrigation systems. Since the development of tractors and inexpensive chemical fertilizers and pesticides, the number of farms in the United States has decreased by sixty-three percent while the acreage per farm has increased by sixty-seven percent, meaning small farms, which farmers of color are more likely to own, have disappeared and large industrial farms have grown in size. Mechanization has had a profound negative impact on small farms that may not have the ability to invest in these new technologies. As Quaresma explained, “the investment for infrastructure in the beginning is very high.” And while support systems exist for beginning businesses and organizations, there is not so much in place for beginning farms. Infrastructure can be a major barrier for a beginning farmer and for already underserved farmers of color, and there is not enough support in place to streamline this process.

The few programs run by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) do not provide adequate support for farmers of color. Quaresma explains that “from the beginning of the country and then over time, this country has been lacking policies

that support people of color in the farming industry.” Among the other countless things the USDA is responsible for, it is in charge of administering programs that can assist farmers in farm safety, ownership, and operation, as well as outreach programs to the socially disadvantaged, veterans, and beginner farmers. It is often difficult for farmers of color who own smaller farms and grow specialty crops to access certain USDA programs when their specialty crops don’t meet tough scheduled planting guidelines. Recordkeeping is more of an oral transfer rather than detailed documentation on some smaller farms, and because records are required to receive assistance, USDA programs do not reach many small-scale farmers of color. The Census of Agriculture’s definition of a “farm” typically involves a minimum amount of acreage and money made in annual sales. Even my family’s farm, which makes a substantial amount of sales each year, has trouble qualifying for programs that hold these same requirements. An article by the Congressional Research Service argues that “previous discrimination in USDA programs has helped to produce these very conditions now used to explain disparate treatment.” The grants that are accessible to small-scale farmers are typically funded by small organizations, but they are limited and very competitive. Application processes are also confusing and time-consuming.

The federal government has also continuously failed farmers of color. In 2021, the Biden Administration included billions of dollars in debt relief for minority farmers in its American Rescue Plan. When white farmers protested, claiming the plan was an act of reverse discrimination, Congress repealed the act and contributed the money to their Inflation Reduction Act for “distressed borrowers.” This term now encompassed all races and ethnicities, appealing to white farmers. It then became nearly impossible for farmers of color to access or receive the money to help relieve debt because they once again faced discrimination. This is the reality for so many farmers of color: a farm’s income often does not compensate for its expenses. This makes it incredibly hard to run a profitable farm. Rancher Leroy Brinkley told Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) that on his farm, “the work is there but the money’s not.” The New York State Agriculture and Markets Diversity and Racial Equity Report revealed that “there are 8,964 farms with white producers generating over $50,000 in farm income, while only 103 farms with BIPOC farmers are generating that amount.” John Boyd Jr., a participant in the National Black Farmers Association, said specifically about Black farmers, “The government has to start living up to its commitment, and they have to start treating Black farmers with dignity and respect.”

From slavery to sharecropping to racially based land theft, farmers of color have been facing injustices in farming since the founding of the United States. Quaresma emphasizes the important resource farming offers our communities. Whether you’re buying community-supported agriculture or getting your milk and dairy products from a local farm, you are supporting an incredible cause. In Quaresma’s words, “farming is such an important service to the community; we need food to eat every day, or else we wouldn’t be

there!” She stated that awareness is one of the most impactful action steps we can take when trying to cultivate more equitable farming opportunities. In Groundswell, Quaresma helps spread information so that we do not repeat past mistakes. She believes that we need to push how important locally grown food is and work to create a more supportive foundation for farmers of color.

The Congressional Research Service has compiled a few considerations for Congress to support farmers of color, such as monitoring how the USDA collects and reports data on race and ethnicity so we are receiving up-to-date accurate statistics, and either amending existing programs or establishing new ones that are more representative of farmers of color. As to how you can become an active member in this fight for farming equity, make sure you’re supporting local organizations who connect with small-scale, or beginning farmers of color such as Groundswell, the Youth Farm Project, and Farming for Freedom. The adversity of racial disparity in farming is an enduring and current issue, but there are many ways we can step in to make a difference.

Farming for Freedom Trail artwork. Farming for Freedom Trail