March is Women’s History Month. What better way to celebrate this than by featuring a few of the remarkable women who have helped shape science and math into the fields that they are today!

Elizabeth Blackburn

Elizabeth Blackburn is an Australian biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2009 for her discovery of the molecular nature of telomeres and the telomerase enzyme. Cells divide through a process called mitosis. But before cells divide, the DNA within the cell needs to be duplicated. It is important that the chromosomes containing the cell’s DNA are copied entirely. If not, vital genetic information can be lost, which can lead to a myriad of problems. Prior to Blackburn’s research, it was hypothesized that DNA sequences located at the ends of the chromosomes, termed telomeres, can serve as a cap, preventing shortening of the chromosomes.

In the 1970s, Blackburn studied a unicellular eukaryote called Tetrahymena thermophila, and found that the ends of Tetrahymena DNA contained a short sequence that is tandemly repeated. Blackburn and biologist Jack Szostak then showed that the repeated sequence in Tetrahymena protected DNA from degradation. Thus, they were able to conclude that these specific repeated DNA sequences aligned with the proposed function of telomeres. Blackburn then worked with Carol Greider in discovering an enzyme that was able to accurately add telomere DNA repeats on chromosome ends. They called this enzyme telomerase, which functions to prevent the loss of DNA internal to the telomere. Without telomerase, telomeres will shorten during each cell division and the chromosomes will begin to degrade, leading to cell death.

Blackburn’s findings showed that telomeres are crucial for normal cell division to occur over an organism’s lifespan. Telomere shortening has been found to be associated with age. These discoveries fueled the idea that increased telomerase activity in cells could help increase the lifespan of an organism. By lowering cell aging, perhaps it is possible to prevent the onset of diseases like Alzheimer’s. Blackburn continues to study telomeres at UCSF today.

Maryam Mirzakhani

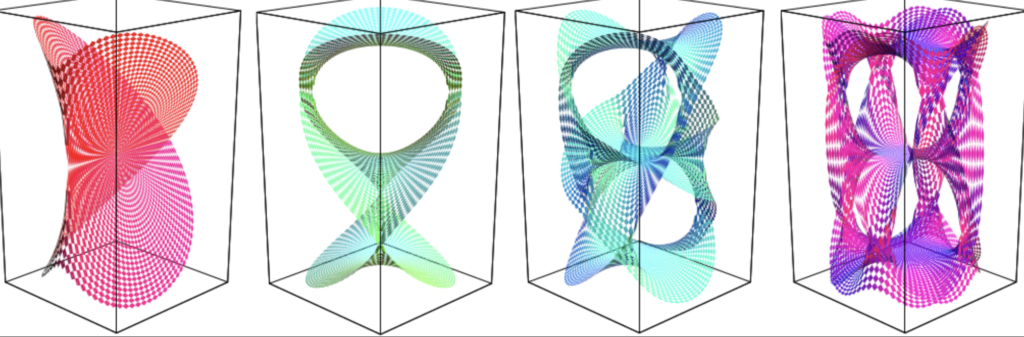

Maryam Mirzakhani was the first woman and the first Iranian to be awarded a Fields Medal in 2014. The Fields Medal is considered to be the Nobel Prize of Mathematics, but it is only awarded every four years. The medal is awarded to either two, three, or four mathematicians under the age of forty, as John Charles Field (the mathematician that the medal honors) wanted the award to both recognize work done and encourage further achievement of recipients and onlookers alike. Mirzakhani won the Fields Medal for her contributions to the dynamics and geometry of Riemann surfaces and moduli spaces. Riemann surfaces are a connected one-dimensional complex manifold (a space that looks like a plane up close but may be different as a whole) such as the ones shown below.

Examples of Riemann surfaces like the ones Mirzakhani studies. Wolfram MathWorld

Mirzakhani specialized in complex theoretical mathematics, including moduli spaces, Teichmüller theory, hyperbolic geometry, Ergodic theory and symplectic geometry. She used this math to describe curved surfaces and their complexities in great detail. The following quote from mathematician Jordan Ellenberg at University of Wisconsin-Madison best explains Mirzakhani’s research to a lay audience: “[Her] work expertly blends dynamics with geometry. Among other things, she studies billiards. But now, in a move very characteristic of modern mathematics, it gets kind of meta: She considers not just one billiard table, but the universe of all possible billiard tables. And the kind of dynamics she studies doesn’t directly concern the motion of the billiards on the table, but instead a transformation of the billiard table itself, which is changing its shape in a rule-governed way; if you like, the table itself moves like a strange planet around the universe of all possible tables […] This isn’t the kind of thing you do to win at pool, but it’s the kind of thing you do to win a Fields Medal. And it’s what you need to do in order to expose the dynamics at the heart of geometry; for there’s no question that they’re there.” While her work appears to be very theoretical and limited to only the field of mathematics, it could have applications in theoretical physics, engineering, and cryptography.

Chien-Shiung Wu

Chien-Shiung Wu was one of the most influential physicists of the twentieth century, and was nicknamed “the First Lady of Physics.” Wu worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II, which was the U.S.’s program to develop atomic weaponry. She developed the process for separating uranium metal into isotopes U-235 and U-238 through gaseous diffusion, worked on radiation detectors and fixed them if they stopped operating, and improved counters for measuring nuclear radiation levels.

Following the war, Wu was offered a research position at Columbia University, where she began investigating beta decay. Beta decay is a type of radioactive decay in which the proton in an atom’s nucleus is transformed into a neutron or vice-versa. When this change occurs, a beta ray is emitted from the atom. Wu’s beta decay research was significant, providing the first confirmation of Enrico Fermi’s theory of beta decay. Fermi’s theory is quite complex, and was the first theoretical effort in describing nuclear decay rates of beta decay via interactions between subatomic particles.

In 1956, Wu was approached by theoretical physicists Tsung Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang who wanted to utilize her expertise in beta decay. They wanted Wu to create an experiment proving their theory that the law of conservation of parity does not hold true during beta decay. The law of conservation of parity is the idea that objects such as subatomic particles and their mirror images behave in the same way but with right and left hand sides reversed. Wu designed an experiment using cobalt-60 (a radioactive isotope of cobalt) at near absolute zero temperatures (absolute zero is -273.15 degrees Celsius or -459.67 degrees Fahrenheit). If the conservation of parity were true, particles should fly off in all directions. However, more particles flew off in one direction, showing that conservation of parity did not occur during beta decay. This experiment is known as the Wu Experiment, and it dramatically changed one of the universally accepted concepts of nuclear physics. As a result of her experiments, Lee and Yang were awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics, but Wu was left out.

Even though Wu wasn’t recognized for the Nobel Prize, she won several other honors, most notably the National Medal of Science in 1975 and the first Wolf Prize in Physics in 1978. Wu has left a lasting legacy on nuclear physics, with her 1965 book Beta Decay still serving as standard reading for nuclear physics.

These are just a few among the many more women in STEM that have had profound impact on their areas of expertise. I encourage you to explore different fields and different scientists to learn more!